The problem with the ladder

Going into a niche too soon isn’t good for business or your career

The traditional "corporate ladder" model, which is based on the idea of developing more general skills and taking on diverse responsibilities as one moves up the ranks, is becoming outdated. Instead, we should be looking for well-rounded junior designers and gradually building up specialized skills in key competencies as we promote them.

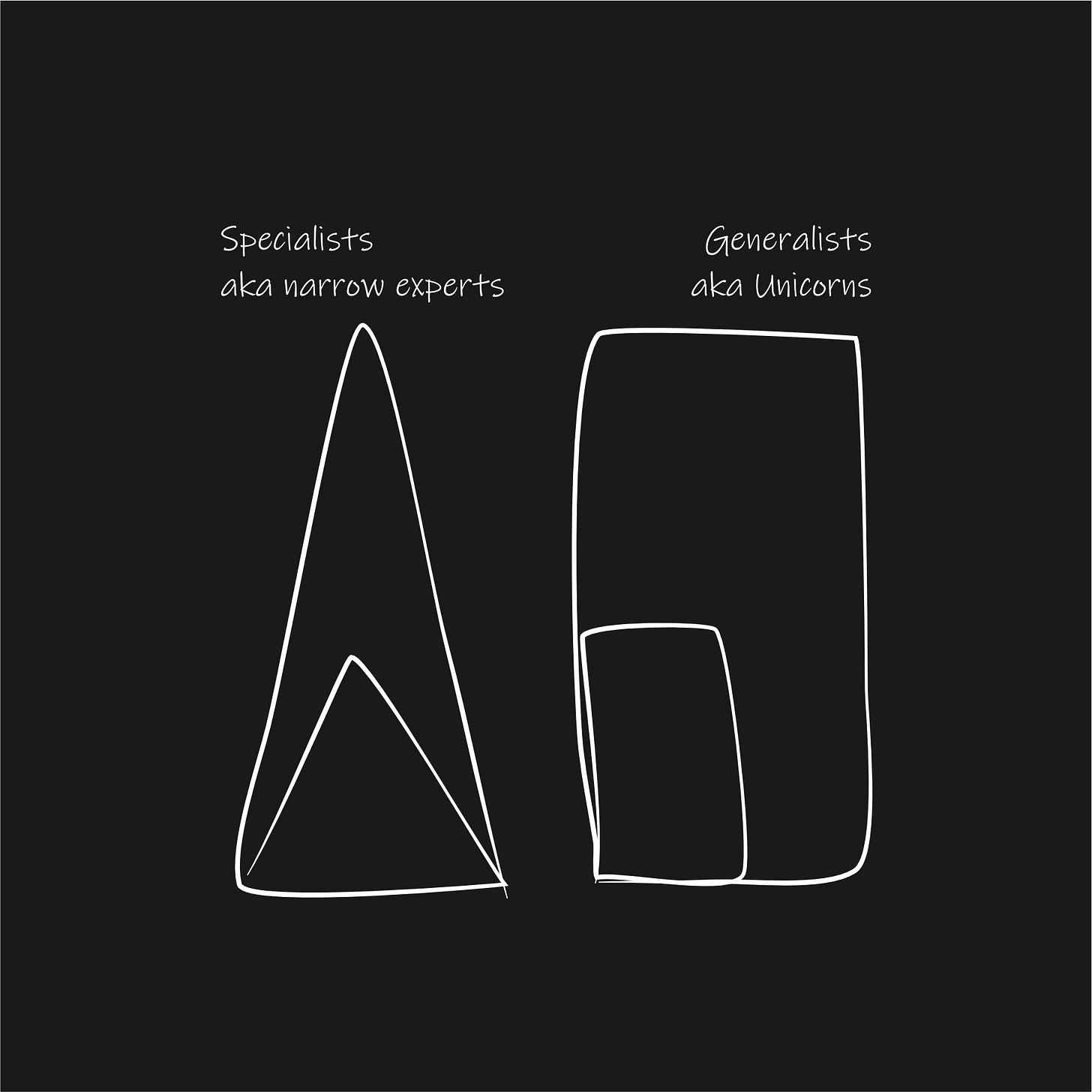

Agencies tend to hire specialists over generalists, particularly at junior levels.

In a job market where there are literally thousands of young designers applying for the same crumbs, it’s little wonder that recruiters, hiring managers and ultimately agency directors are looking for ways to filter the portfolios landing in their laps.

And on the surface, it makes sense.

As a leader I’m always looking for the best I can, especially considering it will be difficult, if not impossible, to change my mind later. And the alternative is to find a generalist who can also delivers amazing designs, while being just as good in a dozen other skills I might be interested in (a unicorn that doesn’t exist).

So why shouldn’t agencies hire specialists? And why shouldn’t you continue to deepen your skills in some obscure niche?

One reason the traditional agency model doesn't work is that it assumes employees already have something they're passionate about, that they’ve already found their ikigai. Being honest, the things I thought I was interested in at 21, are not the same thing that interest me now, and I can’t say I’ve yet found that elusive raison d'être. Forcing young designers to specialize early can lead to disappointment and disillusionment.

Specialization can mean we can charge more for their time, especially in highly focused niches, and it is easier to direct them or replace them if they seek other opportunities. But what happens when requirements change or when we promote that individual? Their specialty may not be transferable to new problems or new roles.

Another problem is that it can create a sense of complacency or unrealistic expectations. "If I learn X and do Y for so long, then you'll promote me to management" - every employee wants things to be this clear cut, but factors like tenure, deepening current skills, and playing to one's strengths aren't good predictors of how well they will rise up to future challenges. For the agency, this complacency can lead to a lack of innovation, creativity, and quality of results, which runs counter to conventional thinking.

If anything is to be taken away from the "don't follow your passions" advice that is so popular these days, going too quickly into a niche might not be a good bet. Especially in a world where today's trends are last month's fads and last year's history. Knowing what specializations will be important in ten years' time (let alone what shape those jobs will take) is extremely difficult to anticipate.

So, what's the mutually beneficial alternative? If we encourage more generalist designers at the lower ranks, agencies need to train and mold them before they can put them to work. And prospective employees will need to compete with even more designers in an already competitive market. Neither of which is ideal.

Instead, we should look to what Tim Ferris calls "specialised generalisation" - having a broad set of competencies with T-shaped skills and experiences in each of them. And, over time, we continue to build on these foundations, making employees more specialized as they take on more and more challenging responsibilities.

For a product designer, this may look something like this: Instead of just focusing on excellent design skills with an interest in some other areas, we should hire the junior designer who demonstrates skills in People, Business, Design, and Analytics to equal degrees. As they become more senior, we prepare them for management and eventually leadership by targeting each competency, providing working experience and skills development. By the time they're asking for that promotion to Manager, you can be sure that, in addition to a decent eye for design, they can also effectively run their projects, their teams, and add insight to their clients. And, if the situation, technologies, or the market changes, they'll be equipped with the skills to meet problems head-on.

So, for young designers, prepare for the future by investing in evergreen capabilities, and box yourself in. And, for agency directors, think about the future partner of your business - do you want the expert in mobile design running your books, or the savvy business man who also knows what the next big change in UI will be?